Democratic Senator Mark Warner recently won his bid for reelection in Virginia over Republican challenger Ed Gillespie. Warner was expected to win by a healthy margin given his incumbent advantage and an under-financed opposition, however, the contest was much closer than anticipated. Warner was considered the most popular elected official in the state while Gillespie, a lobbyist, was running for office for the first time.

The low turnout and changes in Virginia’s partisan makeup could have spelled a loss for the Democrat if Gillespie had received more support from the national Republican Party. In the 2014 election, 42 percent of Virginians turned out to vote. Mark Warner won reelection by only 18,000 votes (0.8 percent of the vote). Nationally, this closer-than-expected contest was one of the major surprises of Election Day as Warner’s margin of victory was far slimmer than Democrat Terry McAuliffe’s narrow victory over Republican Ken Cuccinelli in the 2013 gubernatorial race (18,000 versus McAuliffe’s 56,000).

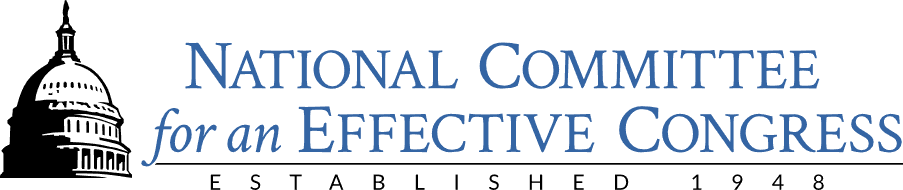

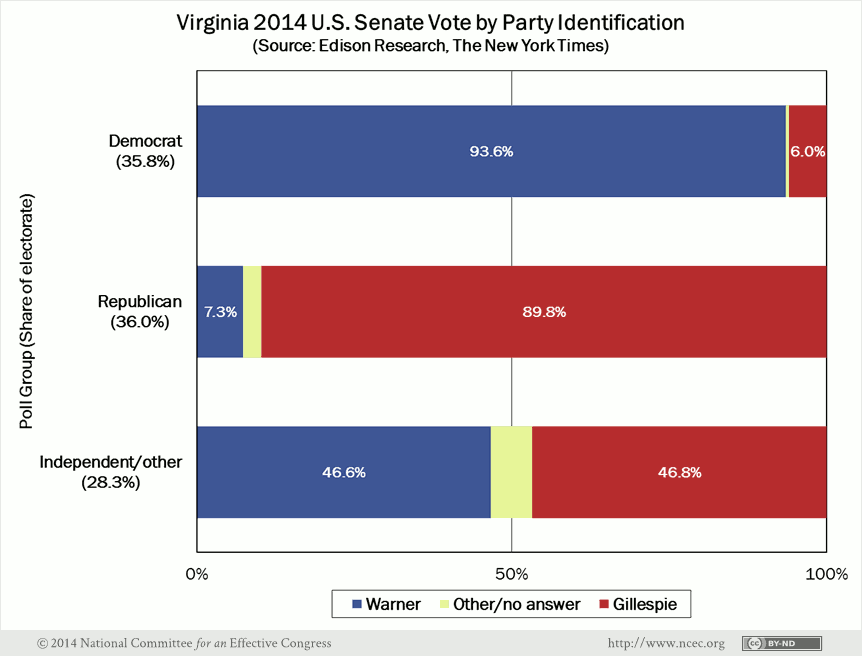

Party and Ideology

The last Democrat to run for Senate was incumbent Tim Kaine in 2012. He won his election by 225,000 votes (6 percent of the vote); however, he was sharing a ticket with President Obama which helped bring Democratic voters to the polls. Warner’s 2014 performance was weaker than Kaine’s in 2012 (49.2 versus 52.9 percent) but slightly stronger than McAuliffe’s in 2013 (49.2 versus 47.8 percent).

The three previous Governor and U.S. Senate races were able to draw “crossover support” from conservative and Republican voters but Warner’s campaign had difficulty replicating this. This change could be the result of a shifting Virginia partisanship—in 2013, Democrats enjoyed a 5 percent advantage over Republicans that has, since, eroded.

In 2014, Democrats and Republicans each represented 36 percent of the Virginia vote. 94 percent of Democratic voters supported Warner together with 7 percent of Republican voters. He saw slightly more support from self-identified conservatives, winning 16 percent of that ideological group. Warner also struggled against Gillespie because he failed to win a majority of the Independent voters; both candidates won 47 percent of Independent votes on Election Day.

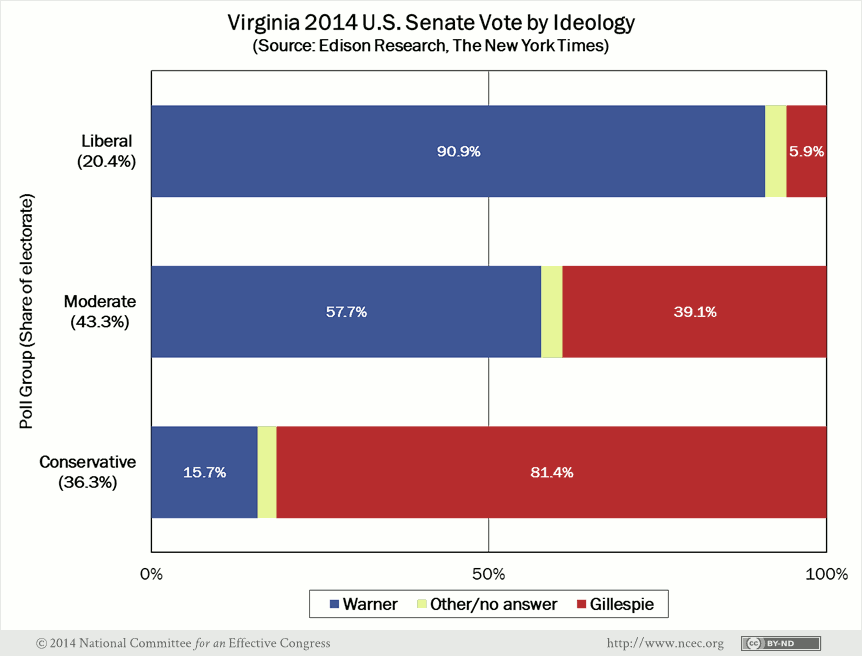

Race and Gender

Warner’s near-demise was highlighted by a shocking lack of support among both white men and white women (losing by 30 percent and 16 percent, respectively). He was saved, though, by overwhelming support from African-American voters, as is the trend for Democratic candidates in Southern states. African-Americans comprised 20 percent of Virginia’s 2014 statewide vote and Warner won 90 percent of this group’s support.

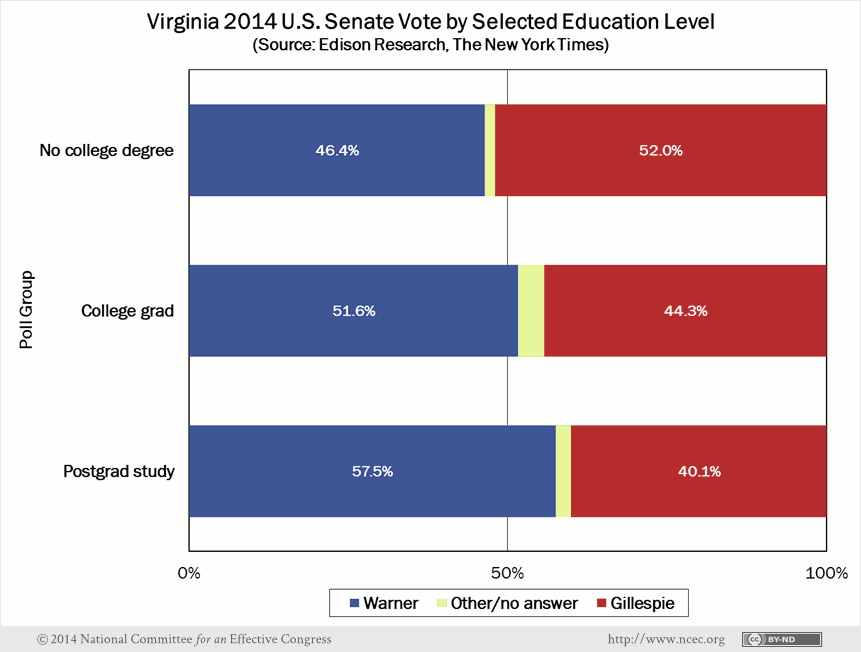

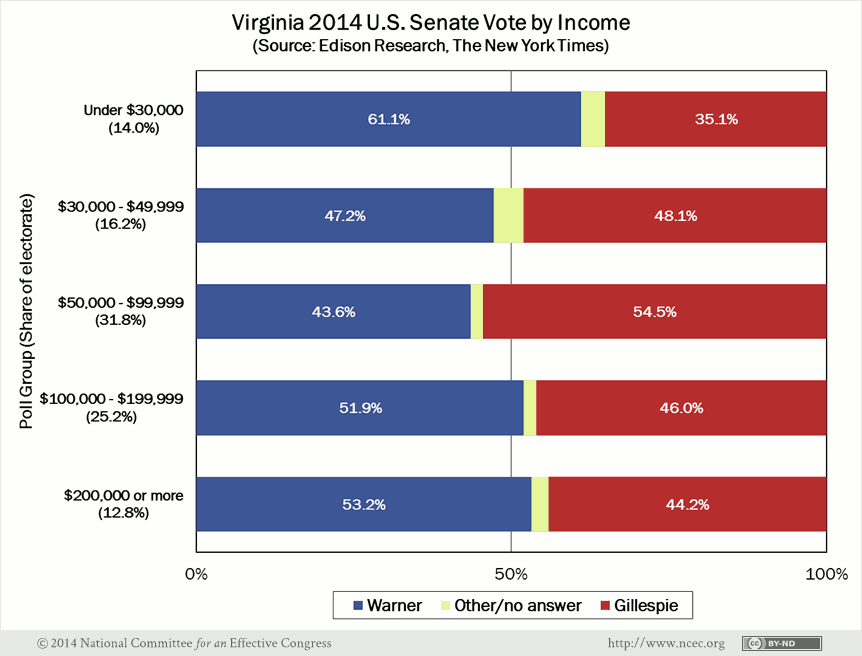

Education and Income

White voters in lower socioeconomic stations preferred Gillespie to Warner, but Warner found broader overall support across many different socioeconomic strata. Warner won by 7 percent among college educated voters and by 18 percent with voters holding post-graduate degrees, but Gillespie won by 6 percent among voters with less than a college education. Gillespie also won a majority of support from voters earning between $50,000 and $100,000 per year. Warner won a majority of support with voters who earned less than $30,000 per year and voters who earned over $100,000 per year.

Demographic Trends

Minority populations are growing in Virginia and the share of white voters in the state is about to plunge below 70 percent. Warner was able to win reelection in a non-presidential year with only 37 percent of the white vote. Warner should be able to maintain viability in future elections with stronger voter-turnout efforts focused toward white Democrats and the African-American population. Democrats will also need to make stronger inroads among Virginia’s Independent and middle-class voters.

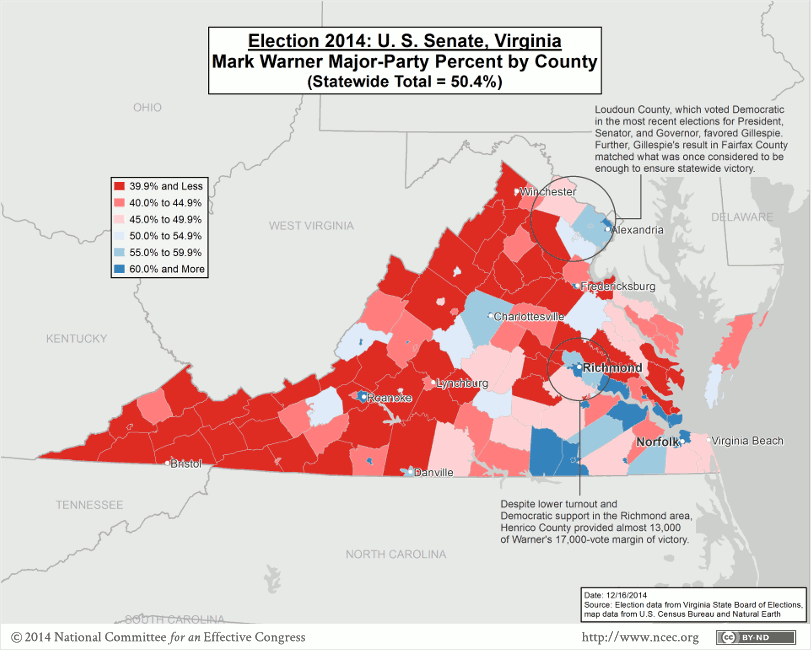

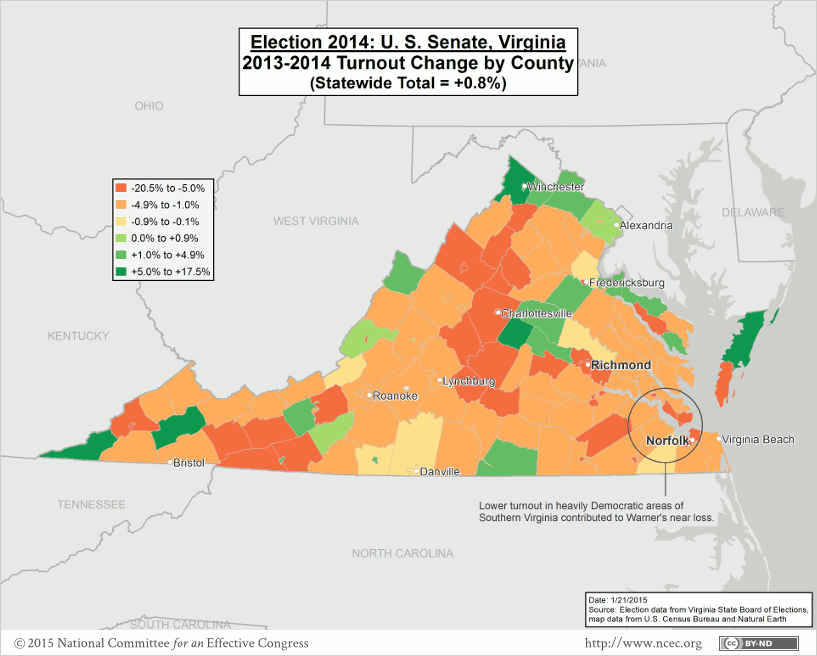

Geographic Overview

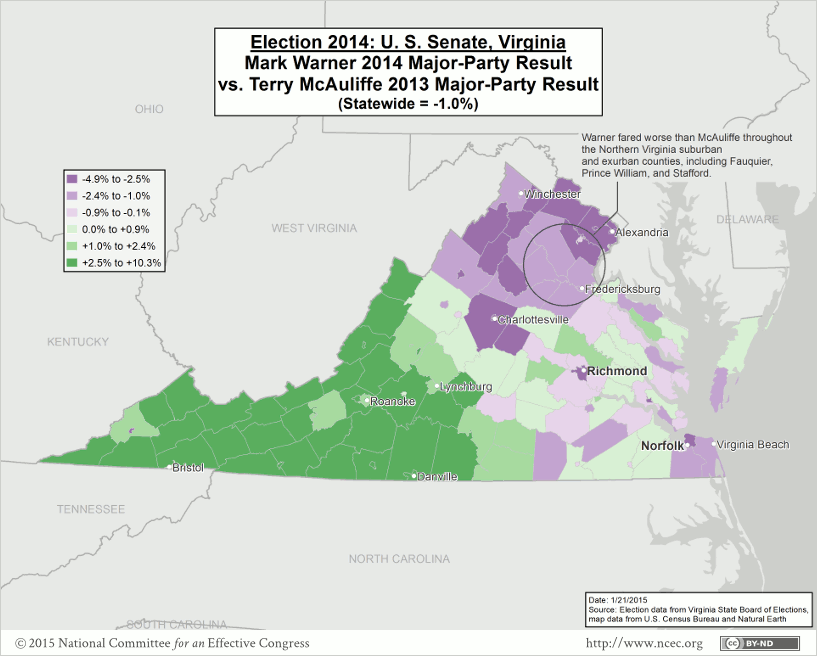

Part of what made Warner’s margin of victory so small was his underperformance in Fairfax County. President Obama, Senator Kaine, and Governor McAuliffe all won more than 60% of the Fairfax vote in 2012 and 2013. Past and current analysis has shown that winning 40 percent of the vote in Fairfax County is the new threshold for Republican success at the statewide level—Gillespie won 41.1 percent of Fairfax. Warner was expected to hold support for Gillespie below 40 percent but was unable to do so.

Loudoun County, a wealthy Northern Virginia suburb, is regarded as Virginia’s “swing county” and it lived up to that reputation. Somewhat surprisingly, Warner lost Loudoun’s major-party vote by a margin of 0.3 percent. In contrast, McAuliffe won Loudoun with a margin of 4.6 percent in the 2013 gubernatorial election. This notable decline in the Democratic vote was not the result of lower turnout—more Loudoun voters cast ballots in 2014 than in 2013. The other peripheral Northern Virginia suburb, Prince William County, also showed less support for Warner in 2014 than for McAuliffe in 2013. Warner won 51.5 percent of the county while McAuliffe won 54.3 percent.

The failure of Warner to amass a plurality in Loudoun, coupled with a less than impressive performance in Prince William County, was a surprise. In the heavily Democratic Arlington and Alexandria counties, Warner was outperformed by McAuliffe due to low turnout and the general assumption that the communities that “turned Virginia blue for Obama” would not need outreach or targeting.

In the Washington, D.C exurbs of Stafford, Spotsylvania and Fauquier counties, Gillespie trounced Warner by margins larger than Ken Cuccinelli’s 2013 plurality. Consequently, there is little or no evidence that minority growth in these counties would blunt the strong Republican advantage in these areas.

Warner may have salvaged this election with his impressive performance in Henrico County, a Richmond suburb, despite the county’s turnout of 5,000 fewer voters. He won 56.8 percent of the Henrico vote; this margin of nearly 13,000 votes made up more than three-quarters of his statewide plurality. In the city of Richmond, a 15 percent decline in voter turnout hurt Warner. Warner won 78.3 percent of the Richmond vote (compared to McAuliffe’s 81.3 percent in 2013).

The heavily Democratic African-American cities in Southern Virginia—Hampton, Norfolk, Petersburg, and Portsmouth—also saw declines in turnout. All four of these cities overwhelmingly supported Warner, as they did McAuliffe, Obama, and Kaine, but thousands of potential Democratic voters in these cities did not go to the 2014 polls.

Chesapeake and, to a lesser extent, Chesterfield (barometers for Virginia’s changing demographics) have experienced an influx of suburban voters in recent elections. In Chesapeake, Warner was able to eke out a 703-vote win, but in Chesterfield, he lost by almost 9,000 votes.

In the marginally Republican Virginia Beach, an independent city in the Tidewater region, Gillespie won by 5,400 votes, more than doubling Cuccinelli’s 2013 margin. Also, as expected, Gillespie trounced Warner in all of the rural portions of the state (Northern Neck, Southwest, etc.). Despite having performed impressively with rural voters in the past, Warner succumbed to the same trend as virtually every other recent Democrat in 2014.

Conclusion

Mark Warner’s incumbent advantage and immense popularity should have given him a comfortable win in 2014. Instead, low turnout rates and a change in Virginia’s partisanship granted Warner an even narrower victory than Terry McAuliffe saw in the 2013 gubernatorial race. Gillespie’s near-victory demonstrated that a conservative Republican, when not perceived to be a party extremist, may still be a viable candidate in a future Virginia election. With more support from his party, Gillespie might have staged the upset of the year in 2014.

Looking Forward

Despite Warner’s near loss, Virginia Democrats maintain some basis for optimism. They now hold both U.S. Senate seats, all three statewide offices, and have won two consecutive presidential elections. A stronger turnout in 2016 will bolster the Democratic ticket, but 2017 may present an opportunity for Gillespie or another moderate Republican to take the governorship back from McAuliffe. Virginia will be a “purple state” once again in 2016, but future non-presidential elections could favor Republicans if Democrats are unable to turnout their base.